Articles by Aileen M. Smith

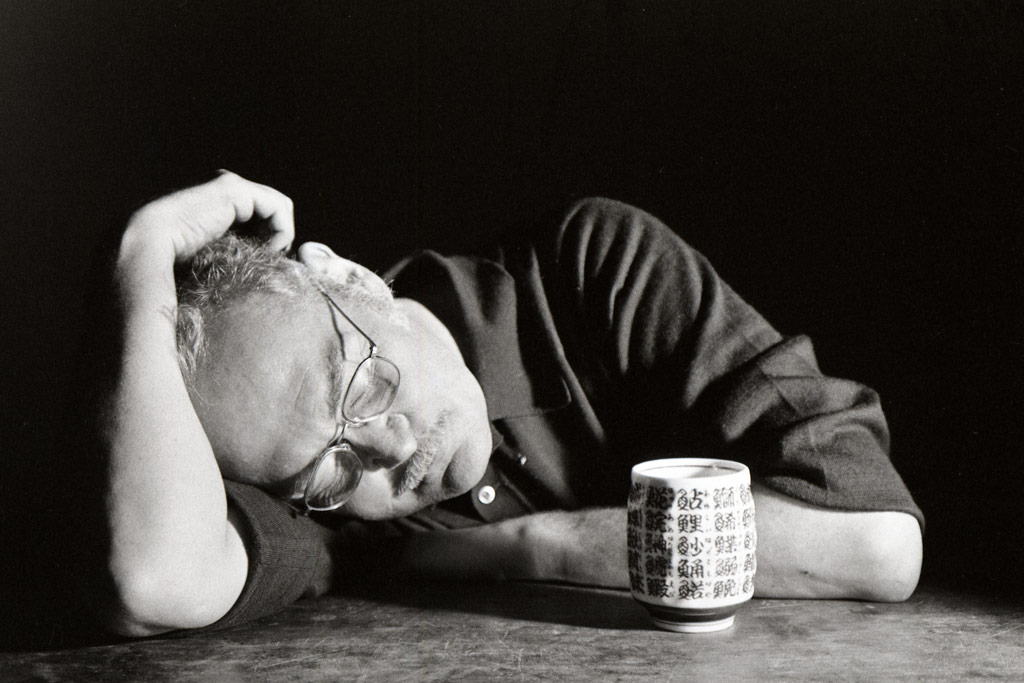

W. Eugene Smith, Photo by Takeshi ISHIKAWA

My Life with W. Eugene Smith — Reminiscences

From:

アイリーン・スミスコレクションW. ユージンスミスの写真

Aileen M. Smith Collection in the photography collection of The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto, W. Eugene Smith photography

Exhibition Catalog, 2008

The National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto

Aileen M. Smith

Co-author, MINAMATA, with W. Eugene Smith

I am grateful to the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto for organizing this retrospective exhibition this year, commemorating the 30th anniversary of W. Eugene Smith's death. Thanks to the museum, Gene is very much alive again in this space and time. The viewer completes the photograph, and so at this moment, Gene's photographs are recreated once again. Gene is indeed a fortunate man.

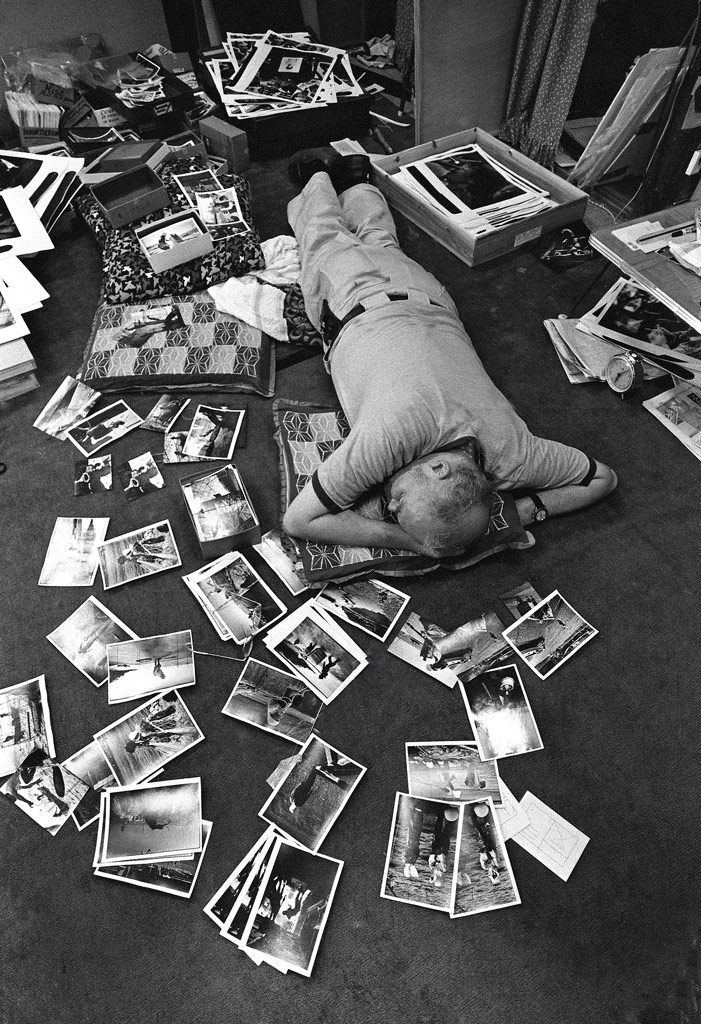

The Aileen M. Smith Collection came about as part of my separation agreement with Gene after our six and a half years of marriage. The selection was made shortly after Gene's death in October 1978, at Gene's archive in Tucson, Arizona, at the Center for Creative Photography. I made the selection based on several criteria: the significance of the image in his career, the excellence of print quality, historic value of the physical print (e.g. prints used for original LIFE magazine publications), etc. Overriding the entire selection process was the requirement that the collection conveys the power of Gene's photographic essays, which he had devoted his life to creating. I also selected a small number of prints for individual sale.

My aim was to keep the collection together, with the hope that at some point it could be acquired by an entity which would maintain it intact, an organization with the ability to give Gene's work high exposure to the public and at the same time preserve it in optimum archival condition. I count it as my good fortune that the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto has become this very entity which I had sought.

I knew Gene toward the end of his career, at the culmination of his life experience. It is difficult for me to write about the process that lead him to this point because I did not experience it directly, but I did live the culmination with him. Although the actual physical time was short, it was intense and, to me, feels like a lifetime.

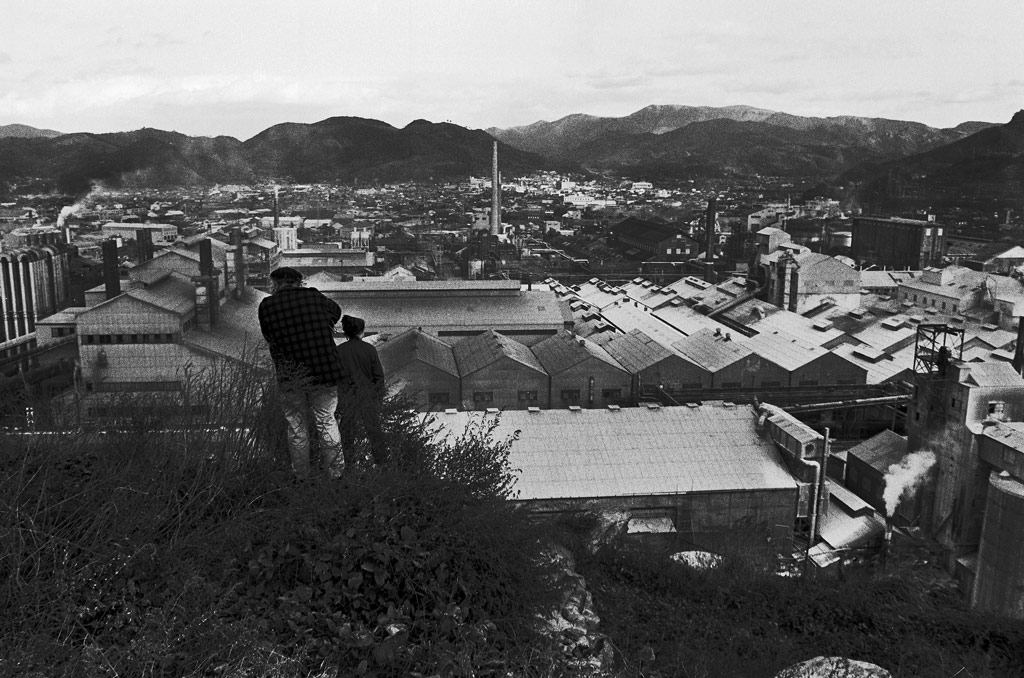

Gene was born in Wichita, Kansas, USA on December 30, 1918. In December 1936, just before he turned eighteen and “jumped this place” (the Midwest) to work as a photographer in New York, he wrote the following in a letter to his mother. “My station in life is to capture the action of life, the life of the world, its humor, its tragedies, in other words, life as it is. A true picture, unposed and real... If I am shooting a beggar, I want the distress in his eyes, if a steel factory I want the symbol of strength and power that is there... I want [my pictures] to be symbolic of something... I realize that this is a pitiful effort to explain my philosophy of photography, but it is out of this haze that the fulfilling of my ambition will be. Long years are ahead, probably years of hardship, but what care I if I can succeed.”

The person I met in that old, dusty loft above Bernie's Hardware, in New York City's garment and flower district on Sixth Avenue between 28th and 29th Street, on that hot summer day in August 1970, was the very same young man who had written this letter. But by then he had experienced those long, hard years and he was 51 years old. I was 20. Gene and I were together from that day on, virtually all the time until 1975. Three years and three months of this time was spent living in Minamata, working together on a work which was to be Gene's last and my first.

Photo by Takeshi ISHIKAWA

The predominant aspect of Gene was his youthfulness. I had never felt so old being with an adult person. Of course all those “long years of hardship” had taken their toll. Gene was depressed when I met him. He was “planning” suicide, working on his retrospective show, the 600-print Let Truth Be the Prejudice, surrounded by a number of young helpers. He said he was going to kill himself after it opened at the Jewish Museum uptown. This was actually nothing new. He had often called friends saying he was going to commit suicide, and his friends would rush over, but he had never actually attempted it. The next years entailed my keeping him alive, yet being exhausted by his youth. Finally, after all these years, maybe I have recovered from the exhaustion, because I am beginning to really miss him.

“Integrity.” That was the core word for Gene; the crucial center. As William Johnson, who archived his work at the Center for Creative Photography, wrote, “Smith wanted to use his photography to fight prejudice and hatred.” Gene would say there was no such thing as “objectivity,” that we all had prejudice and therefore we were all subjective. The most important thing was to be as honest and as fair as possible. His hope was that our pre-judgements, our prejudices, would become as close to the truth as possible. It was important to be honest and say you were subjective. If you said you were “objective,’" you would be lying to yourself and others.

Another conviction was that “art” and “journalism” were not in conflict with each other. Both were equally important to truly attain photojournalism. Gene’s conviction was that as a photographer his responsibility was to his subject and the viewer, and that his responsibility to his editors would be met through the process of meeting these two key responsibilities. This was no easy matter, and it led him to regularly clash with his editors. So, to make all of this happen, you had to fight for it. Every single photo essay of Gene’s was the result of having intensely, passionately fought for these convictions.

Photo by Takeshi ISHIKAWA

The core of the 18-year-old youth who wrote that letter to his mother had never wavered, but he had been changed by World War II in the Pacific. After he had witnessed and photographed the war in Saipan, Gene wrote to his family on September 3, 1944, “…For these people of the pictures were my family — within possibility — and I saw my daughter, and my wife, and my mother, and my son, reflected in the tortured faces of another race. Accident of birth, accident of home — damn the rot of men that leads to wars. The bloody dying child I held momentarily in my arms while the life fluid seeped away and through my shirt and burned my heart into flaming hate — that child was my child…."

This was the Gene I knew. Johnson writes, “On Saipan, Smith learned to compose in a powerfully coherent way so as to put himself (and therefore the viewers sharing his stance) within the emotional sphere of the action.” That was exactly it. That is how we photographed in Minamata.

When we first met, during the summer into autumn of 1970 at the New York loft, these are the convictions he poured his heart out about, in front of the hundreds of proof prints of the Schweitzer photo essay of Lambarene, Africa, on the second floor of the loft. The story had been warped by the editors at LIFE back in 1954. That is why he had quit LIFE.

This was the time to finally make it right. It was the same with all his other photo essays. With Puccini’s La Bohème filling the air, he persuaded me as though reinstating what had been destroyed by the censors during the war, the editors at LIFE, all the realities of life, and the business of photography. It was right before we first heard about Minamata. We spent months in the darkroom, printing in the blood red light with the music on. Janis Joplin. Miles Davis. Verdi and more Puccini. Exposing, dodging, burning in, the smell of developer, hypo, ferrocyanide in the air. He would rub negatives on his nose, his eyes twinkling, laughing and saying, “Nose grease!” before inserting them in the enlarger. He would rub his hand on his leg in pain — World War II pain — and then grab me and dance around with the music just a moment while we had the print in the hypo. Gene agonized over the negatives of Spanish Village which he had “lost" — fortunately they were later found in a box with old, no longer used dentures.

He wanted his exhibition to be the ultimate symphony. Gene kept popping dexedrines supplied by two doctors, neither of whom knew the other existed. (This was constant, exhibition or not. In Japan it was ritalin.) The half-dozen of us worked in a frenzy — Gene, and the rest of us mostly in our 20s. I remember staying up five and a half days with only an hour and a half of sleep during the last stretch. The guy who had cut the hundreds of frames to custom size arrived at the empty museum with me. Looking at the room after room of empty halls with just the two of us there, quiet and frantic, he said, “Aileen, we are going to have to hang this show on our own! Gene is never going to make this happen!!” But Gene did… arriving, giving instructions from an old wooden wheelchair as he moved from print to print, scotch in hand, laying out the prints like music, attaining perfection... the closest he could come to before heaven.

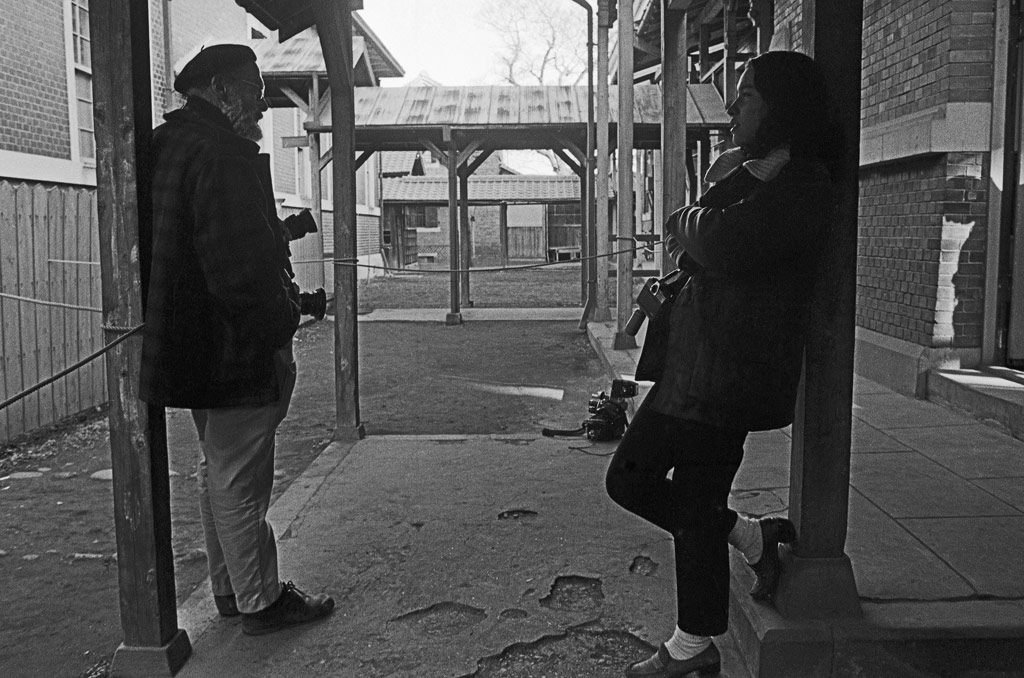

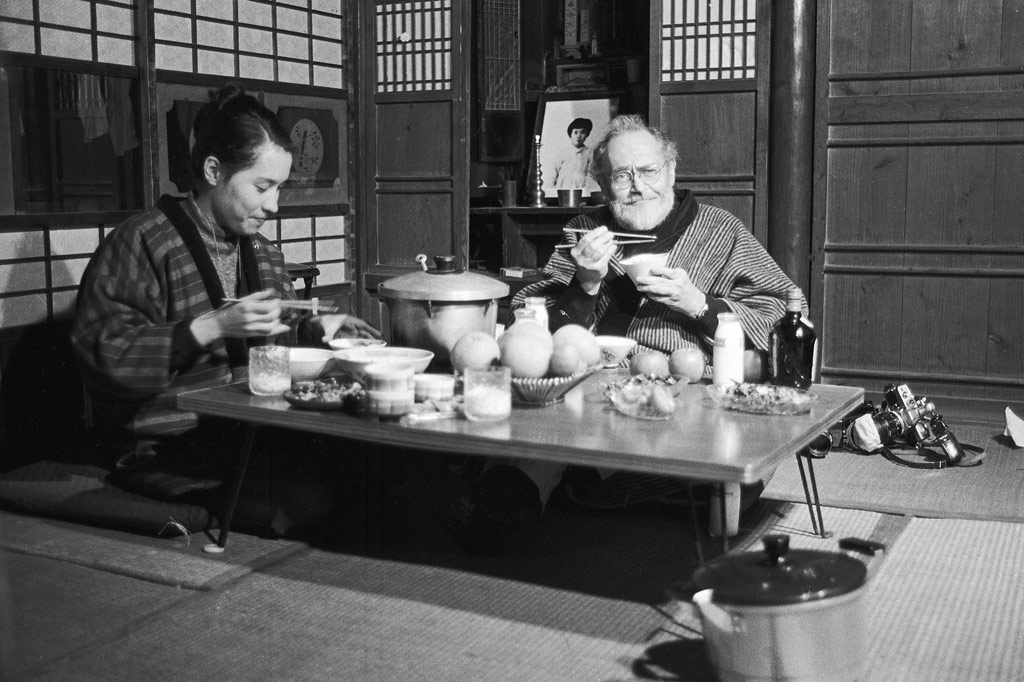

W. Eugene Smith and Aileen Mioko Smith, Photo by Takeshi ISHIKAWA

And then we encountered Minamata, thanks to Kazuhiko Motomura, the same man who had made Gene’s Let Truth Be the Prejudice exhibition become reality in Japan in 1971.

And so it went for the next four years. Sprinkled with all-nighters, always a rollercoaster. New York City, Harajuku in Tokyo, Minamata, Los Angeles... and back to New York.

Gene brought everything to Minamata, both the convictions and the baggage that he had amassed over the decades. He integrated that with the ideal, necessity and compromise of working with me. In every major photo essay of Gene’s, there is someone or some people, mostly invisible, who were an integral part of making his goal become reality. Up through the LIFE years, it was his family who provided this essential element.

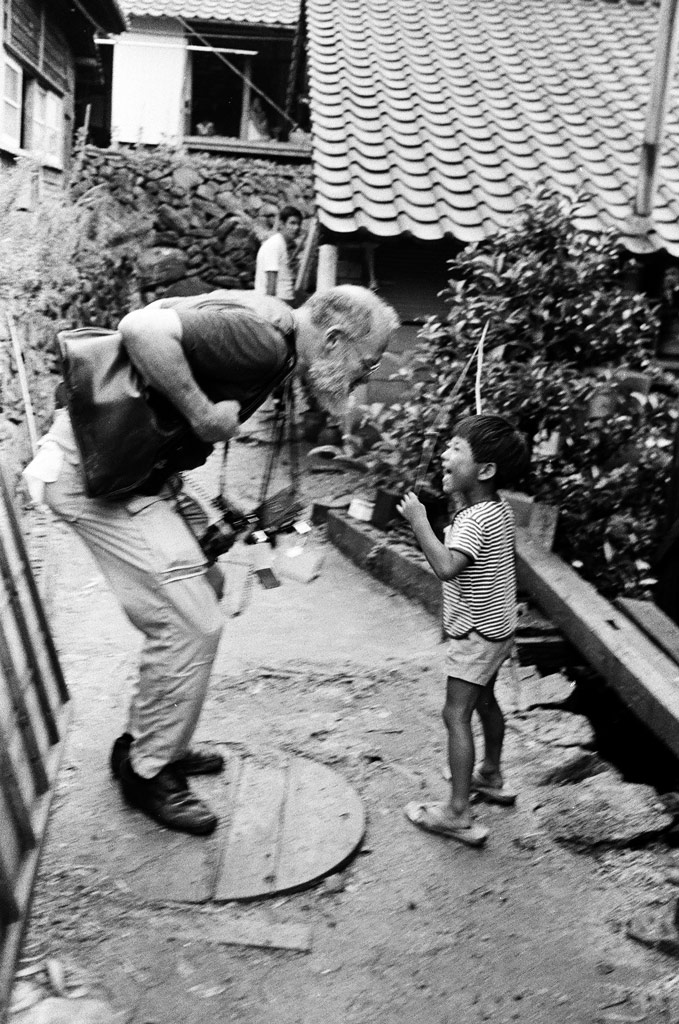

Gene’s core was integrity and humor. His savior complex was tempered by this humor. During his three years in Japan from 1971 to 1974 he was continually telling jokes, mostly puns which wouldn't translate into Japanese, but everyone we were photographing loved them anyway. Shyly swinging his body back and forth, Gene would say, with a twinkle in his eye again, that he was full of Kansas corn. “I’m just a country boy!” he would say, as he sipped his teacup full of scotch. In the evening, our landlord, who had lost a daughter to the mercury poison of Minamata Disease (her altar was in our bedroom), might come over to our house from next door and the two tipsy men would start line-dancing arm-in arm, our landlord singing an old Japanese military war song, “Saraba Rabaul...until we come again!” with Gene joining in, followed by Gene’s rendition of the blues, “I went down to St. James infirmary... ! saw my baby there.” In the meantime, I would be worrying about making sure the ashes from the firewood in our earthen-floor kitchen area would not cover our negatives hanging there, or getting the cameras ready for the next day.

Photo by Takeshi ISHIKAWA

Gene had a barrel chest and was by no means a tiny American. However, as he himself said, he was like a mouse when he photographed. The night before, he would have taken hours wrapping his leg which had a permanent open wound right above the ankle, his skin discolored and deteriorated with what he told me was years of malnutrition after quitting LIFE magazine. (The actual wound was from a beating he had suffered right before I met him.) He would fumble around for ages with the bandages, then in a super-inefficient way with camera filters and equipment, until we could finally go to sleep to prepare ourselves for the next day. Gene only learned a couple of words in Japanese, he would not have been able to repeat our home address to anyone, he just knew our phone number , and barely that. I went everywhere with him.

Much of the time, Gene and I would photograph simultaneously. And in the evening, when we developed the photographs, I would take into my hands his negatives which revealed a man crystal-clear in his mind, with a skill that built up methodically, repeatedly to the two to three frames which would convey what we wanted to say. The negative frames had a rhythm just like the jazz and opera Gene loved. They ebbed and flowed, building up to the shot that he was looking for. It reflected his breathing in and out before holding his breath for the shot. And mine, mine depicted my own personality and experience. And then we ate our supper. Of course he would hardly eat anything because of the injury in his mouth from the shrapnel wounds he sustained during the war in Okinawa. Gene had a hole in the top of his palate and a full set of false teeth by the time he was in his mid-20s . When we were together, his daily calorie intake consisted mostly of a bottle of Suntory Red scotch (a liter would last one day), 10 glass-size bottles of milk, both of which we got from a little shop one minute away, and sometimes a raw egg, orange juice, or Carnation Breakfast nutrition powder.

W. Eugene Smith and Aileen Mioko Smith, Photo by Takeshi ISHIKAWA

Gene knew this would be his last work. He knew he would not have another chance. He planned it magnificently, so well that I never once felt any doubt about the direction of its execution.

Physical pain always accompanied our life. First it was the war injuries, then shortly after we arrived in Minamata, it was from injuries inflicted by goons of the polluting chemical company, Chisso, that we were photographing. This latest injury entailed his fainting when he lifted his arm up, my dragging his body by the feet to the side and continuing to photograph. Once his head and eye was in so much pain that he was screaming in the middle of the night for me to get the ax next to the bath and cut his head open. This all mixed with other former injuries — two plane crashes, and what he told me was saving someone in a traffic accident, a sacrificial-type sadistic beating, mugging, etc. — he was a body full of pain.

We published the Minamata story abroad for the first time in LIFE magazine’s June 2, 1972 edition. This was Gene's last work in LIFE, and he had really wanted this photo essay to work — this time once and for all. He negotiated fervently with the editors. The day we received the published copy, I wept. They were hot, angry tears, because LIFE had mauled the story. The title, “Death-Flow from a Pipe,” had never been discussed, and the editor’s comments about our coverage of the story were fiction made from thin air. I will never forget what Gene said to me. He said “But hon, this is the best I’ve ever gotten.” That is when I realized Gene was not just a dreamer but a realist.

We completed our book Minamata on January 7, 1975, thanks to Larry Schiller in Los Angeles. Without his business ability and making us finish the book, it would never have become what it is.

On the back cover of the Minamata book Gene wrote, “Photography is a small voice, at best, but sometimes — just sometimes — one photograph or a group of them can lure our senses into awareness. Much depends upon the viewer; in some, photographs can summon enough emotion to be the catalyst to thought. Someone — or perhaps many — among us may be influenced to heed reason, to find a way to right that which is wrong, and may even be inspired to the dedication needed to search for the cure to an illness. The rest of us may perhaps feel a greater sense of understanding and compassion for those whose lives are alien to our own. Photography is a small voice. It is an important voice in my life, but not the only one. I believe in it. If it is well-conceived, it sometimes works. That is why I — and also Aileen — photograph in Minamata.”

In mid-October 1978, more than three years after we had separated, Gene called me from Tucson, asking me to be with him again. He said, “You could play tennis here. Maybe we could go to China…" I said, “But I don't want to play tennis.” I heard later that over those few days, he had also called many others, his loved ones, his friends. Gene died from a stroke — his second-a day and a half later, on October 15th, having lived, indeed, a full life.

W. Eugene Smith and Aileen Mioko Smith, Photo by Takeshi ISHIKAWA

- Aileen Mioko Smith

- Apt. 103, 22-75 Tanaka Sekiden-cho, Sakyo-ku, Kyoto 606-8203 Japan

Telephone: +81-75-701-7223 Facsimile: +81-75-702-1952

Email: contact@aileenarchive.or.jp

http://aileenarchive.or.jp